Semey is a lot of things. It is the place where Kazakh national poet Abai spent a considerable time of his life. It is where Dostoevsky lived for a while, and even had his first marriage. It is near where the Soviet Union tried many of its nuclear weapons, back when the place was called Semipalatinsk. It is yet another one of the former Tsarist trade cities that were most often found alongside some of the mightiest rivers of Siberia, this time along the banks of Irtysh, much like Pavlodar. Yet today, Semey is, Semey. It is a city of its own rights, and in many ways, one of the finest places where you can see the changing face of Kazakhstan, the direction its going towards, and the one is pivots away from. Join me, as we go through my two days long expedition to this Eastern Kazakhstani city.

Much like its other post-Soviet counterparts, Semey has its own Victory Park, dedicated to the fallen soldiers of the Great Patriotic War. The one here is quite small, and devoid of grandeur. It seems like a few items that were exhibited here are no longer present as well, adding to a feeling of abandonment. Other than the small eternal flame in the middle, and a well-preserved T-34 tank that greets you in the entrance, this flying soldier may be the best attraction in the whole park.

For those that are into Soviet heritage, Semey offered something else, something unique. Noticed the past tense? The city used to be the host of a so-called “Alley of Lenins” where around twenty busts of Lenin and Marx were on display, gathered from all around the country after the collapse of USSR in 1991 in an effort to preserve the statues in one place. This apparently changed in either late 2023 or early 2024, when “something” happened to the alley, minus this one statue. Some say the rest have been destroyed, some others think that they are undergoing renovations. I sure hope that it is the latter, but with all its nostalgic charm, Alley of Lenins sure became a fragment of the past now.

Semey’s fire department still openly carries its red star, which was a nice reminder of my time in Kazan, where I could see it in a few places. It is also a good-looking red brick building, and there are some old Soviet-era tools inside, though I could not get a closer look at them given the fact that the site is still used actively.

Soviet past is not the only past Semey is known for, in fact, its Tsarist, or should I say Tatar heritage is the one that may be of more interest to more tourists these days. City is home to a sizeable Tatar quarter, where you can find colourful wooden houses. They are old, older than USSR for sure, and are organized quite neatly. There are also a few mosques like this one, sporting a similar architecture. These are especially a treat for the eyes.

This is how the Derevyannaya Mosque looks from the inside. Women would pray upstairs as the men prayed below them. The whole blue theme naturally continues inside too, and there are a few ancient heating systems that are not in use today but must have saved the prayer times in winter back in the days.

Speaking of cold, it was certainly cold when I visited Semey. This was not planned, but then again, I did nothing to avoid it. I had to go somewhere during my spring break, which coincided with Nowruz in Kazakhstan. I assumed the birth of spring would be a warmer time to travel, alas I was mistaken. As you can see, the Irtysh River, which I saw in all its proper glory a few months ago in Pavlodar, is hardly thawing in this photo.

Feeling the burn of cold winds on my face, but willing to explore more of this small city, I ventured deep into an island that lays in the middle of the river. This is a sizeable landmass, one with an open zoo and some monuments on it, as well as tracks for running and cycling. Semey, back when it was called Semipalatinsk, was near the proving grounds of Soviet nuclear experiments. Kazakhstan has perhaps one of the most proactive anti-nuclear movements in the whole world, and that is one of the reasons why. This monument, called “Stronger than Death,” is dedicated to all those that suffered from the Soviet experiments near the city, and presumably beyond, as similar tests were run across the globe by rivalling powers.

Having had enough freezing air in my lungs, I made it to Semey’s art museum named after Nevzorov, the second biggest collection of the country according to many. I can confirm that it had more pieces in it than anywhere in Astana has to offer, though compared to Almaty’s Kasteev State Art Museum, it is barely a drop in the ocean. Nevertheless, I really liked the vibe of this place, with a ton of artists at work early on in the morning. I also appreciated their efforts to make almost everything trilingual and go a step further to make some “blind-friendly” exhibits in almost every room, so that all can enjoy the art here to a certain degree. You do not see that very often.

Just a few hundred meters away from the former museum is a museum-house where Dostoevsky once lived in. He not only lived in Semey, but even had his first marriage. He would converse with his Kazakh friends, like Shoqan Walikhanov, and also work on his writings as a writer often does.

This museum consists of three parts. A temporary exhibition, one that was about male fashion when I visited it, a permanent exhibition that is a proper literary museum dedicated to Dostoevsky and his works, and the actual house where the writer once lived in. It has been years since I last read his works, and I am hardly the person to talk about fashion, so it is safe to say that it was the last bit that really attracted me to this place. Seeing the table where the man himself actually worked on at some point was certainly something.

Semey is a small city, so, just a few hundred meters more and you will arrive at the Local History Museum, which has this amazing map on display. I mean, just look at it. It is supposed to tell you about the way Turkic tribes migrated centuries ago, but that is not why it is fun to look at. Look at South Africa, then look Malaysia and Indonesia. Well, if you can find them…

Okay let us be serious once again. Nevada and Semey are, surprisingly, similar places. Nevada-Semipalatinsk International Anti-Nuclear Movement is the evidence for that. Since both places suffered the brunt of nuclear experiments, anti-nuclear sentiments run high among both locales. A small part of the exhibition in the local museum is dedicated to this chapter of city’s recent history. It is nowadays nigh impossible to visit the actual proving grounds, as it remains irradiated, and because of some other reasons that I am not entirely sure of. However, even flying above it and seeing the destruction from above made me realize why people dedicated their entire lives to this cause, it sure is a just one.

Abai was not born in Semey, not in the city centre that is, but he sure lived here for a long time. He is the national poet of Kazakhstan, and even a national hero of sorts. There is a so-called Abai’s Road that starts from Semey and leads to many locations where the poet once visited or lived in, a journey that I am sure some of the more literary or nationalist locals embarked on at least once in their lives.

Semey may just be the start of that road, but it also has, possibly, the best museum on Abai. Here you can see anything from the carriages he once used to his entire genealogy painted on walls. You can also listen to some of his verses in Kazakh, while its translations run through your hands if you keep them in a certain position.

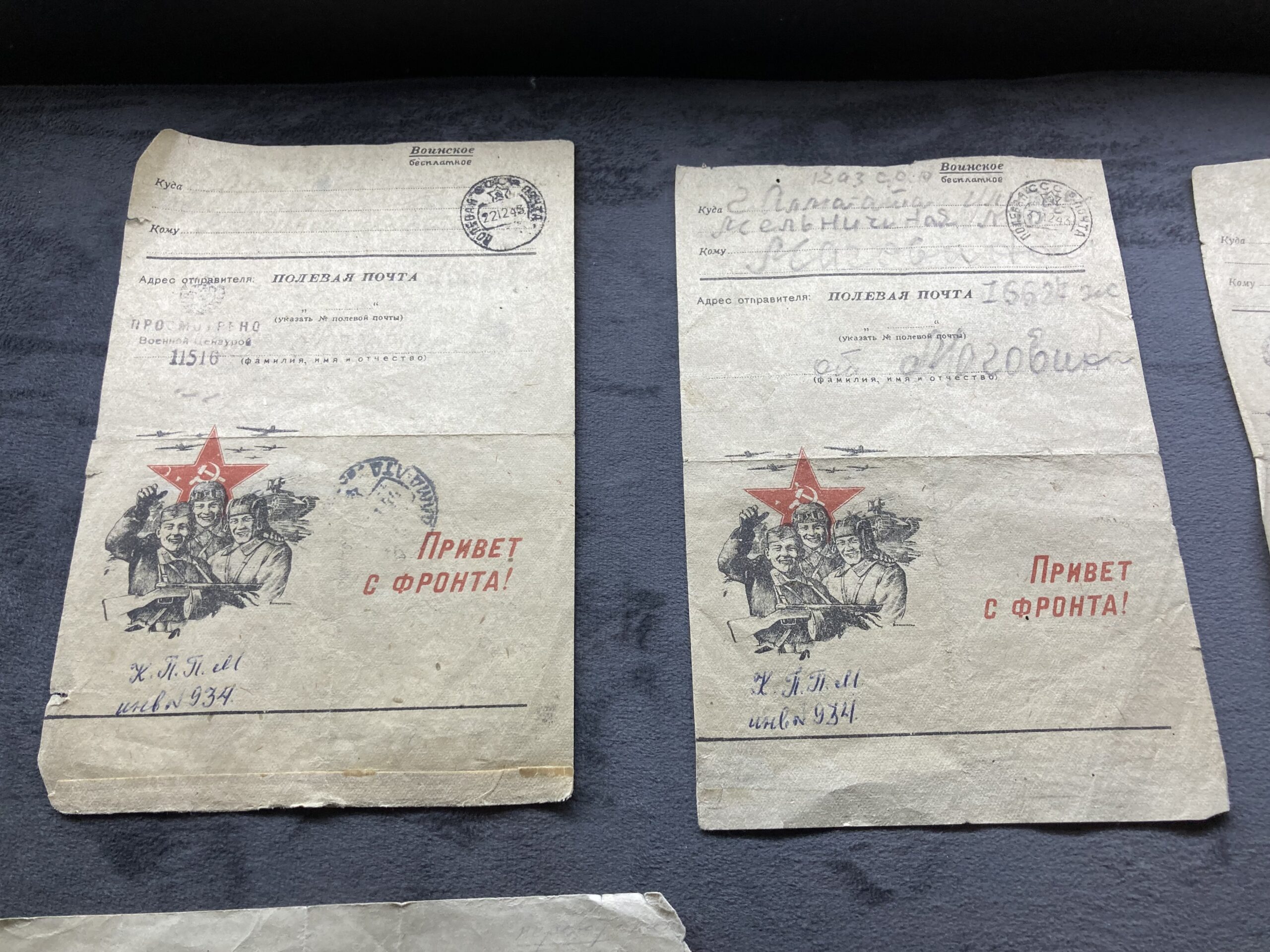

However, I think that the museum staff here can be a bit better. It would be preferable if they did not answer a “why” question with a simple “no” when I asked why the third-floor exhibition was off limits. In any case, I even got to find these superb postcards that were sent from the frontlines by descendants of Abai, so I cannot complain. I got my money’s worth.

Though Abai is likely the first thing that comes to any Kazakh’s mind when they think about Semey, and though the city seems to be home to a mostly Kazakh speaking population, there is more to it than it meets the eye. The Soviet legacy is still there, more than it is in the South, or even other nearby cities like Pavlodar. Mosaic hunt in this small town yielded better results than much bigger cities like Shymkent and is only surpassed by the likes of Almaty and Karaganda.

Semey does not have the quantity, but mosaics it has, are top tier. They kept their colour, are certainly cleaned from time to time, and are not short of tender loving care as I saw others that come and get their shots taken when I was trying to find a decent angle myself.

This hunt of mine brought me to the more suburban areas of the town, as it often does. At that point I realized that I had been seeing cars like this a tad too often here. I say cars like these because there are not the limousines most of us are used to from Hollywood movies, but an almost “Soviet” take on it. I for one do not understand their appeal, and though they must be used for something.

After a brisk walk in the cold, I finally made it to the last mosaic on my list, one that certainly blew me away. A lack of sun in this instance is not doing the photo any favours but do trust me when I say that it was bursting with vibrant colours.

These walks on the perimeters of the city also put me in close proximity to hidden gems like this. Just as Z signs were more readily available on the outskirts of Belgrade, one could find more of those that follow a less popular ideology as they leave the city center of Semey. Murals dedicated to USSR, wishing for its return, waiting patiently, are found scattered across the city. This one is more less a shrine dedicated to USSR as the whole shack is covered on all sides with writings like these.

As some look into the past for comfort, some others look forward. Despite its colourful mosaics, and a seemingly renovated Lenin statue, Semey is going in a very non-Soviet direction, to say the least. It is now Abai’s town, Alash’s city, a Kazakh border settlement. Surely there are those in it that would disagree with these changes, but they remain a silent minority. It is the only northern city where Kazakh seems to be spoken more than Russian, and in fact at times I felt like I was back in Shymkent due to the sheer number of people that preferred to converse in Kazakh rather than Russian. It is the front of modern Kazakhstan’s nation building process, with its shiny new Abai Museum, and ever so cheery locals that speak Kazakh at every chance. Without access to Soviet nuclear test sites and the former Alley of Lenins Semey may have lost its charm to some, but do give it a shot, and you may be surprised by what you find at the end.