As a historian, visiting museums is a natural part of any trip I partake in, though such pleasures are often shadowed somewhat by the decent restaurants and pubs that I stumble upon during my travels. Whether that is because the foodie in me is stronger than my historian “side” or if it is due to my high expectations from museums that I am lucky enough to visit is up for debate. When it comes to these wonderful collections, Albania is situated in quite a bizarre position. It would not be right to argue that it has a lot of interesting and superb museums, however, to be fair, given its size and its tumultuous recent economic and political history, what it offers in terms of quantity and quality is not too shabby. I also feel a bit like they are intended more for tourists than locals, with their (often) high prices and tourist-full corridors. Let us now dive deeper into the museum scene in Albania one by one to see what they offer individually.

National Historical Museum in Tirana

Operating since 1981, the National Historical Museum of Albania, located in Tirana, is hardly an old institution. However, with that excellent mosaic on its front facing wall, one could forget all about its age. If only I could see it myself as well! Due to the recent pandemic, quite a lot of museums in Albania, and all around the world for that matter, are under renovations. This is for the better, as once the real tourist tide comes in, they should find all these places and more in a better condition than when I have seen them myself. It was quite unfortunate for me though, as in almost all the museums covered in this short guide, I had to make do with some unexpected shortcomings like this.

National Historical Museum truly takes its name to heart and tries its best to be “good enough” for it. For 500 leks, you do not only find out more about the history of Albania but also get a lecture about turning said history into an extremely nationalistic narrative. In fact, it is home to what may be one of the most nationalistic perspectives when it comes to framing the past, and this means something coming from a guy who read his fair share of studies on nationalism and its thorny scholarship. Once you understand this “nationalizing” and for the lack of a better word, overtly patriotic mission of the museum than all its displays start making more sense.

Moving along the more or less official Albanian stance on the issue, the museum makes efforts to show the connections between the ancient Illyrians, that inhabited these parts of the globe eons before the term Albanian came to be used for the people that live there, and the modern Albanians. After spending an entire floor on these more ancient and then medieval societies, it is interesting to see that a rather long part of the Albanian history, one that saw its mountainous geography became a part of the Ottoman Empire, was almost skipped in favour of the more “Albanian” parts of the region’s recent past. This is not surprising, as all the “post-Ottoman” states that I could visit so far embraced a similar attitude towards the time these countries (or their “proto” versions) were ruled by the Porte. It is quite unfortunate, as it would be an interesting experience to find out more about how Albanians reflect upon such historical matters today in more details, alas, that could not be the case.

There may not have been much about the Ottoman rule in Albania, and its impacts to the region, but there sure was an exceptionally interesting though a bit short display on Skanderbeg and his insurrection/rebellion/crusade/national cause. I kid you not when I use all these words as all of them were in fact used to describe the same events that took place in the mid-15th century. Obviously, the more “negative” descriptions often come from more pro-Ottoman sources, whereas the more “nationalistic” readings are a product of mostly Albanian and/or Western scholars, with even more terms being used by both parties or other parties that study Skanderbeg and his military campaigns against the Ottoman Empire. It truly makes one appreciate the usage of the term “arts” in the Bachelor and Master of Arts diplomas that I received in history, and not “science.”

Speaking of nationalism, and how this museum is the perfect example of an institution that serves to historically legitimize some of the more modern causes that the Albanian state is invested, we should look no further than to the selection of maps that accompany all the displays (or pavilions as they were often called) in the museum. Starting from the exceptionally early periods, so once again from the ancient Illyrians, one can see that the likes of Epirus (at least the northern parts of it, some of which lay in Greece today) and Kosovo (a partially recognized state that is de jure a part of Serbia today) were almost always made a part of the “Albanian” world. It is not a new trick in the book by any means, and in fact, a trained eye can spot such “narratives” laying all around in most museums around the globe. However, it is quite important to note that, nonetheless.

What surprised me the most about the museum was not what it included but perhaps what it did not as silence itself often has a lot to tell if you know how to listen to it. There is pretty much nothing about Albania or its history after the WWII, with the notable exception of a pavilion on “Communist Terror” and another one on “Mother Teresa.” Modern Albanian take on its communist past, for understandable reasons, quite hostile. However, it being so hostile that there being no real museum or whatsoever to learn more about the less bloody parts of Enver Hoxha’s rule in the country is most unfortunate. As the reader will realize quite soon, this theme of showcasing the worst that communist regime resonates with in Albania is quite common in all its museums in the capital, and such displays stop very short of attempting to teach their visitors more about the everyday life in the country, and other everyday issues that many would be interested to find out more about.

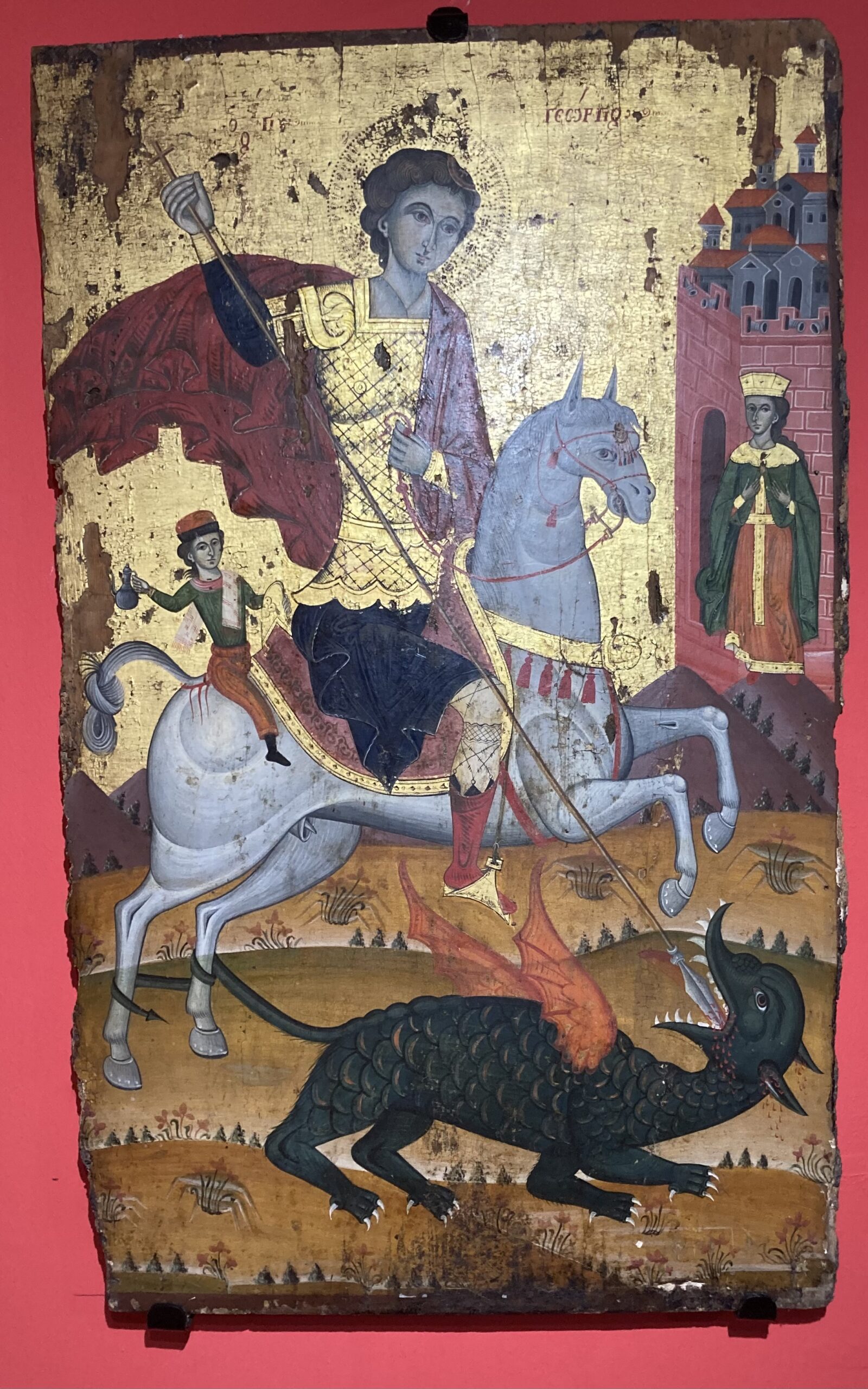

I must say, the small but extremely gorgeous collection of icons found in a dedicated pavilion in this museum is reason enough to go and visit it! I do not know much about Medieval Albania, and certainly even less about Christian religious icons, however, it was a well-designed and decently illuminated room with a very satisfying collection that I am sure many would find enjoyable to at the very least peek at quickly.

With its rather reasonable price tag, a sizable collection that can take up to two and perhaps even three hours to go through (though the three hours would mean reading pretty much anything that you can find in English), and central location, the National Historical Museum in Tirana is a must go if you visit Albania. It would be even better once the renovations are complete, more emphasis is given to proper English translations of many artefacts on display, and perhaps also retrieving some of the originals of many documents and items that are originally displayed in many different museums around (mostly) Western Europe. None of these are “deal breakers” per se, but at the very least an improvement in English-language availability of most information found in the museum would be extremely appreciated by many.

Bunk’Art 1 in Tirana

Often regarded as one of the best destinations to visit in anyone’s Tirana itinerary, there is both very little and also too much to write about Bunk’Art 1, that is found on the outskirts of the Albanian capital. It is an Enver Hoxha era anti-nuclear war bunker complex, truly a behemoth with many layers and hundreds of rooms, that was later turned into an interactive museum with numerous historical and artistic installations set in it to better illuminate the tumultuous history of the Communist Albania, though once again with a focus on the less savoury parts of it. There is not much to talk about it, because it is, for the most part, an audio-visual experience where one truly must be there to appreciate what it offers to the fullest. Also, it really is a must visit spot, so spoiling many of its beautiful displays will not do you much good if you ever visit it yourself.

On the other hand, I do want to write at length about it, not only because I almost left it by shedding some tears of joy after feeling like I just found what one might call the Disneyland for history buffs, but also because it left me with even more questions than it answered, which is always a great thing! Well, it is so, for me. That is often how interesting stuff works, they reel you in further the more time you spent trying to appreciate them. Alas, I will limit myself to sharing a few photos with short commentaries on some of the displays that you can find in Bunk’Art 1, and to sharing a word of warning about it: it is cold down there! It is not freezing or anything, but coming from a sweltering outside, after a rather long walk from the city centre during high temperatures, I was quite taken aback by just how cold the tunnels of Bunk’Art 1 were. It is best to bring along something other than shorts and shirts to wear there, and that is what I realized most groups with a guide did!

The entry to the Bunk’Art 1’s ticket office is through this tunnel, which itself sets the right mood for this wonderful museum’s many visitors by being all dark and mysterious. Of course, it is but a prelude to what awaits you on the inside.

This is the true entry to the museum, after you buy the ticket to get in. You just need to walk 200 meters or so from the ticket office upwards along some other bunker-related doors and utilities. Later, I would find out that most of those doors were just emergency exits for different floors of the bunker complex.

Enver Hoxha’s own room (for times of emergency, which never came to be) can be visited as part of this museum, and it should be interesting to note that by visiting it a couple of times you would already be more invested in it than Enver Hoxha himself, which, if I remember the text correctly, only really visited it once. After all, this entire bunker was made for emergencies, such as a nuclear war, which thankfully never materialized. While a part of me is extremely grateful for such a wonderful reality, the other part cannot help but ask if this useless addiction to “bunker-building” and the mind-boggling price tag that it had for the Albanian people could not have been used for better endeavours?

It is important to note that since this bunker was built around the 1970s, after the Soviet-Albanian split, and around the time when Sino-Albanian split was gradually happening. This meant that the majority of “science-heavy” instruments that are found in the bunker, such as its heating subsystems and electricity infrastructure were either fully or partially bought from the People’s Republic of China, which is why it is so common to see many “Chinese” characters all around the numerous rooms, corridors, and corners of this underground megastructure.

There are many thematic displays to be explored in Bunk’Art 1, so do not be surprised when you find more themes than you can possibly think of when you make your way there, such as this one on chemical weapons and their use in the communist-era Albania. What is even better is that certain rooms have temporary displays, to be replaced with something new sometime soon, and there were some new displays under construction when I was there in the summer of 2022. It seems like one can visit the Bunk’Art 1 time and time again and never get bored doing so with how the Albanians are trying to better that experience for its many visitors regularly.

Bunk’Art 2 in Tirana

Bunk’Art 2 is, for the lack of a better term, the smaller but more artsy brother of its “number one” counterpart. I say number one because for me, Bunk’Art 1 offers a much better experience than Bunk’Art 2, however the latter excels in a few things that may tip the scale for a certain type of clientele. First and foremost, it is found in a more central location, right in the centre of the city, just a bit behind the Ethem Bey Mosque. Instead of having a broad focus, the museum here focuses on the Sigurimi, meaning “safety” in Albanian and referring to the secret police service in the communist-era Albania and its extremely horrifying but interesting history. This bunker complex is much smaller than the former one, hence this more focused temporal and thematic approach complements its limitations the best. However, it seems to be even better maintained than the former, and the English language information available to its visitors is far better translated here. So, though it looks smaller and is so physically, expect to spend around a similar time that you spent in Bunk’Art 1 here, if you intend to properly study the displays, and enjoy the many artistic instalments that you can find all around its three main corridors.

It goes without saying but due to its central location, and it being much closer to the surface, there are no issues or whatsoever with the “heating situation” in this bunker, with temperatures being much warmer than the former in general though not as hot as outside. It is, however, much more crowded than the first Bunk’Art, which can be a dealbreaker to some as it, in certain cases, truly makes it hard to appreciate some of the information that is found in the museum, since sometimes you cannot even find the time to read certain boards due to all the people flowing around you. It may be best to go there as early as possible, when there would be a minimum number of visitors. Let me conclude my remarks on this wonderful piece of art, yes that is what I call such decent museums, by sharing two photos of it before moving on with the rest of my remarks on Albanian museums.

If anything, it looks a bit too inviting from the outside for an emergency bunker for government officials, most of which would work in the ministries that surround it in this photo. The cute tower to the right is obviously a miniature that is put there to invite more tourists downwards.

There are a lot of original pieces of equipment that the Sigurimi used to spy on “enemies of the state,” and it was a joy to see them all whilst reading about their capabilities and how they would often be used.

House of Leaves in Tirana

If you had a “great time” finding out more about the atrocities that were caused directly or indirectly by the works of the Sigurimi, then you should be thrilled to know that just on the opposite side of the road from where you leave Bunk’Art 2 lays another important Albanian museum to visit, called the House of Leaves. As I already (overtly) hinted at, it focuses on the Sigurimi once again, but more specifically on spycraft and how it all really worked out back then, beyond the simplistic spy movies that you may or not may not be familiar with. There may not have been any James Bonds in Albania when Enver Hoxha was in charge, but the tactics Hoxha’s secret police used to track down those they wished to capture for spreading anti-communist rhetoric or for smuggling contraband in and out of the country were mind boggling to read about on their own rights.

Though a bit pricy at 700 leks per person, this award-winning museum (2020 Council of Europe Museum Prize) is a must visit the next time you are around Tirana. Not only is its contents are extremely interesting, but also it is very well organized and properly put together with information in decently translated English being readily available. Though some of the best features of the museum are impossible to photograph (there were plenty of rooms with long excerpts from old Albanian propaganda movies in which one could watch real Sigurimi members explain their spying operations in great detail) let me share with you fine people just two simple photos from this museum too to give you a hint about what you can expect to see there if you end up visiting it.

From the tiniest of “bugs” for surveillance to clunky CCTV monitors, one can find anything that was used for spycraft during the time of the communist regime in Albania. Almost all the displayed items are the original, and there are often texts to explain just what exactly are they and how they were used.

Although the museum was dedicated to spycraft, much like Bunk’Art 1 it too had a very small but much appreciated display about everyday life in a communist-era house in Tirana. Of course, the inhabitants of this house would be much luckier than their rural counterparts when it came to their amenities and their overall availability. Seeing that an entire room full of Albanian made furniture, and even a locally designed and produced TV as well as radio was a joy to say the least, certainly not something one can see every day in most countries one would visit.

Armed Forces Museum in Tirana

How I wish that I could mention the wonderfully built tanks or meticulously put together rifles in this part of this article, alas, that cannot be as I simply could not get into the Armed Forces Museum in Tirana. Hence, this is more of an informative warning to those that want to visit it. Apparently, you need to send a mail to them three to four days before your planned visit, so that they can chaperone you inside the Ministry of Defence complex, in which the museum itself is founded. Do not be like me, circling around the ministerial complex that is guarded by plenty of heavily armed soldiers as you try to find a way to get past them. You cannot. You need to have someone come and get you inside, at least that is what I am told. I did not have the extra time to wait for an answer from the museum, so I could not see what this (I am sure) wonderful museum held. If you want to be successful at your own attempt to visit it, please refer to the link below for more information.

Registration for the Armed Forces Museum in Tirana

The National Iconographic Museum “Onufri” in Berat

Icons are good and all, and as you can guess from my appreciation of them in the National Historical Museum part of this article, I have no issues with them. What I find bizarre is how it is “forbidden” to take a photo of such pieces of art with a phone (without any flash etc.) when you already paid 700 leks to get into a small chapel full of them. That is what happened to me in this museum. The icons you can find in “Onufri” are some of the bests I have ever seen, almost all with their own explanations and a rather handy but short two-sided printed material to accompany you in understanding the rest of the art scattered around the chapel. The rule to not have any photos of them are quite bothersome though, as that was not the case in other parts of the country to my knowledge.

Furthermore, without the audio guide, which many who are not truly into iconography would not pay extra for, one could spend, at most, fifteen to twenty minutes inside. That is quite short for 700 leks, which gets you a meal for two in a truly local Albanian restaurant, or a decent pizza in a good pizzeria which too can feed two people depending on their appetite. I hate to be a broken record here but being able to take a photo or two to look at afterwards and to contemplate on, or to show my art historian friends for further explanations etc. would have dramatically improved the value that one can get from this museum. I did see many visitors taking photos in there despite that rule, and a quick Google Maps search can show you many such photos, so it being reinforced haphazardly (and to someone with an iPhone SE at his hand) was quite absurd in my opinion.

It is, nevertheless, a great spot for those that are seriously into iconography, for the rest of us, I would rather spend the cash on ordering a few more bottles of cold beer alongside your lunch in Berat. Of course, if money and time are not an issue, then simply visiting it for a short time could not hurt when you visit the castle of Berat.

National Museum “George Castrioti Skanderbeg” in Krujë

What is there to say about this museum? Skanderbeg, Albania; Albania, Skanderbeg. These words complement each other quite well, if not perfectly, so seeing this museum will complement your Albanian trip perfectly as well, heck, it is imperative that you see it if you go ahead and visit Krujë, which you can find out more about HERE! It is true that even the famed sword and helmet of Skanderbeg cannot be “truly” seen here, as their originals are on display in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna. However, and although this is very hard to explain in writing, I think that it is the best museum out there to truly capture the essence of Skanderbeg and his legacy.

In fact, it feels more like a shrine than anything else. The very spirit of the Albanian nation, and its foundations can be traced back to Skanderbeg and his deeds, the hardships of which are best understood when one walks around the halls of this beautiful castle and its decently sized courtyard overlooking half of Albania. Perhaps I was a bit too moved by the displays here due to the simple fact that I had just completed a long and tiresome trek to the Shrine of Sari Salltik that sits atop the hill that rises above Krujë, and hence was feeling quite euphoric. Nevertheless, it is one of those museums that is best visited than read about for sure. Once again, it works almost like a grand tomb, a shrine of some sort for Skanderbeg, but due to who Skanderbeg is, his legacy, and its importance for the current Albanian national formation, it also functions like a crib for the modern Albanian identity and its statecraft.

It is a joy to see this museum even from the outside, thanks to the architecturally pleasing castle that holds its many artifacts in it. Unfortunately, most of these artifacts were not the real deal. Nevertheless, replicas or not, it was a joy to see all those relics that were relevant to Skanderbeg and his legacy.

Other than many items of importance, the museum hosts numerous pieces of art that depict some of the most crucial events that Skanderbeg could fit into his legendary life. His achievements were nothing short of extraordinary, and though one can quickly understand how the geography surrounding the Krujë Castle somewhat made it “invasion-proof” to certain Ottoman advances, it becomes clear that the whole operation could hardly function as smoothly as it did if Skanderbeg was not there to oversee it in the first place.

Now that you know more about Albanian museums, which are good and which are meh, what they excel at and what can be improved about them, what better time is there to simply give them a visit? If you are not a museums-person and prefer the outdoors, go ahead and check my works on Albanian highlands and lowlands HERE!